The Real (And Insane) Story Of The Dodo

Its ecology, behavior, extinction, and how we can bring it back to life

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) is an extinct flightless bird that once roamed the island of Mauritius. Since then, it has become a superstar, with iconic appearances like in the Ice Age movies.

Its existence also became a symbol of extinction and the destructive behavior of humans. Despite this, what the general public believes about this animal is shaped by myths. So, what’s the real story about this flightless bird?

We take Hume's (2006) seminal work to share some evidence of one of the most amazing creatures that once cohabitated on our planet.

Mauritius, a Unique Island

Islands are cool.

Why? Because it makes species evolve in isolation, leading to a beautiful and unique diversity of animals. This was also the case for Mauritius, a volcanic island in the western Indian Ocean. Although early Arab traders, followed by the Portuguese, probably found the island first (North-Combes, 1971), they were “rediscovered“ by the Dutch in 1598 (Moore, 1998).

In 1598, Hendrick Dircksz Jolinck led one of the explorations of Mauritius, and it was probably there that they described the Dodo for the first time:

“we also found large birds, with wings as large as of a pigeon, so that they could not fly and were named penguins by the Portuguese. These particular birds have a stomach so large that it could provide two men with a tasty meal and was actually the most delicious part of the bird” (Moree 1998, p. 12).

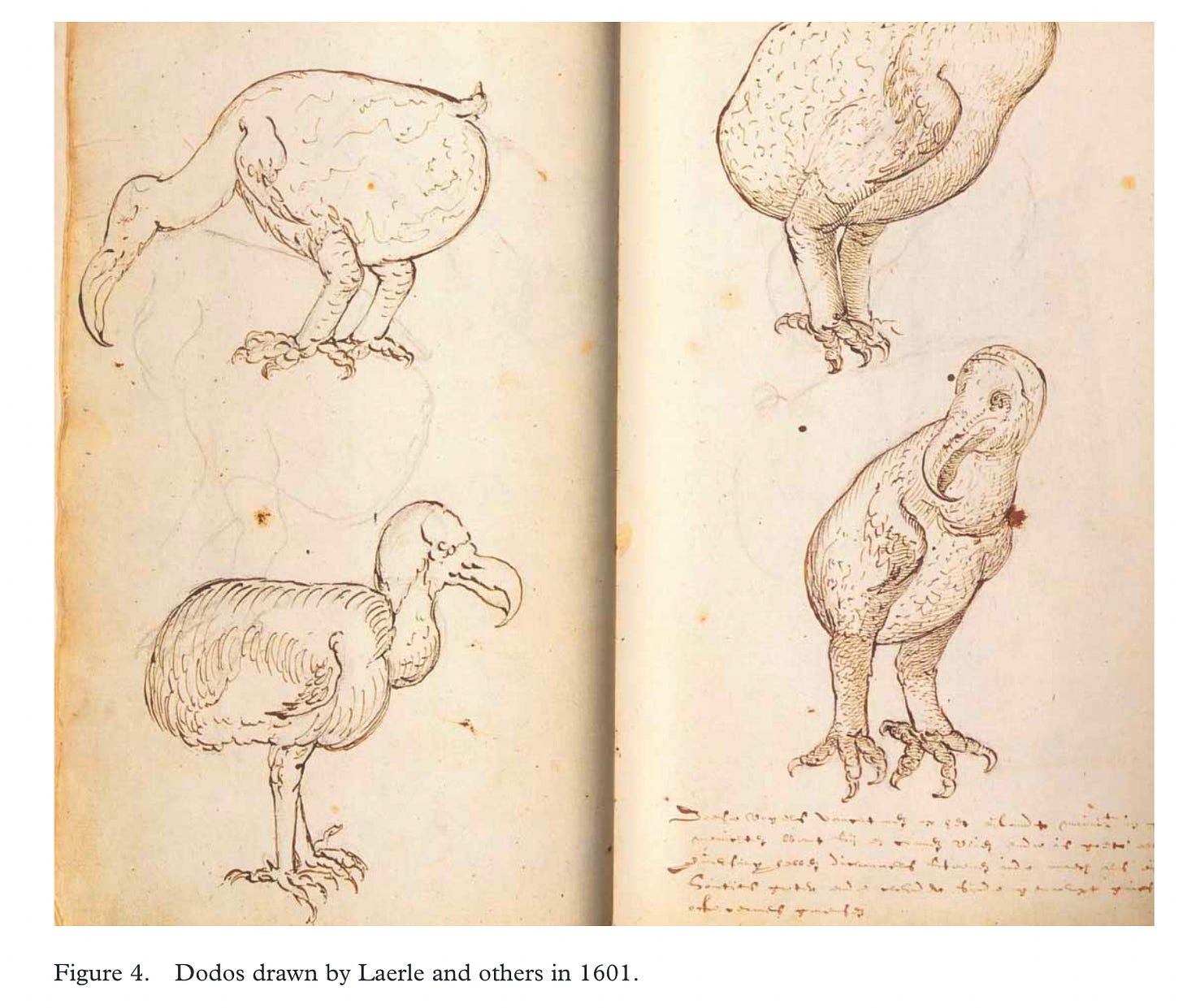

This also came with some of the first drawings about Dodos reviewed by Hume (2006):

But how was this island? Was it only surrounded by dodos? Well, not really.

Before humans arrived, Mauritius was covered by forests and animals. Sadly, because of deforestation and the introduction of invasive species, little remains of what Mauritius was once, and many species are still threatened. Take Jacob Granaet’s letter in 1666 as an example:

“Within the forests dwell parrots, turtle and other wild doves, mischievous and unusually large ravens, falcons, bats and other birds whose names I do not know, never having seen before. This wilderness serves as a shelter and lair for the cattle (which have large humps near their necks), for harts, hinds, goats and pigs (which destroy the young cattle running wild everywhere), and for the tardy tortoises whose livers and eggs are great delicacies, and whose fat (with which the garrison is amply provided) is very healthy and good food and otherwise.

Water-fowls such as geese, teals, waterhens and flamingoes are found among the marshes, very numerous, especially the teals which are so tame they can be killed with sticks; all are fat and pleasant to eat.” (Barnwell 1948, p. 42).

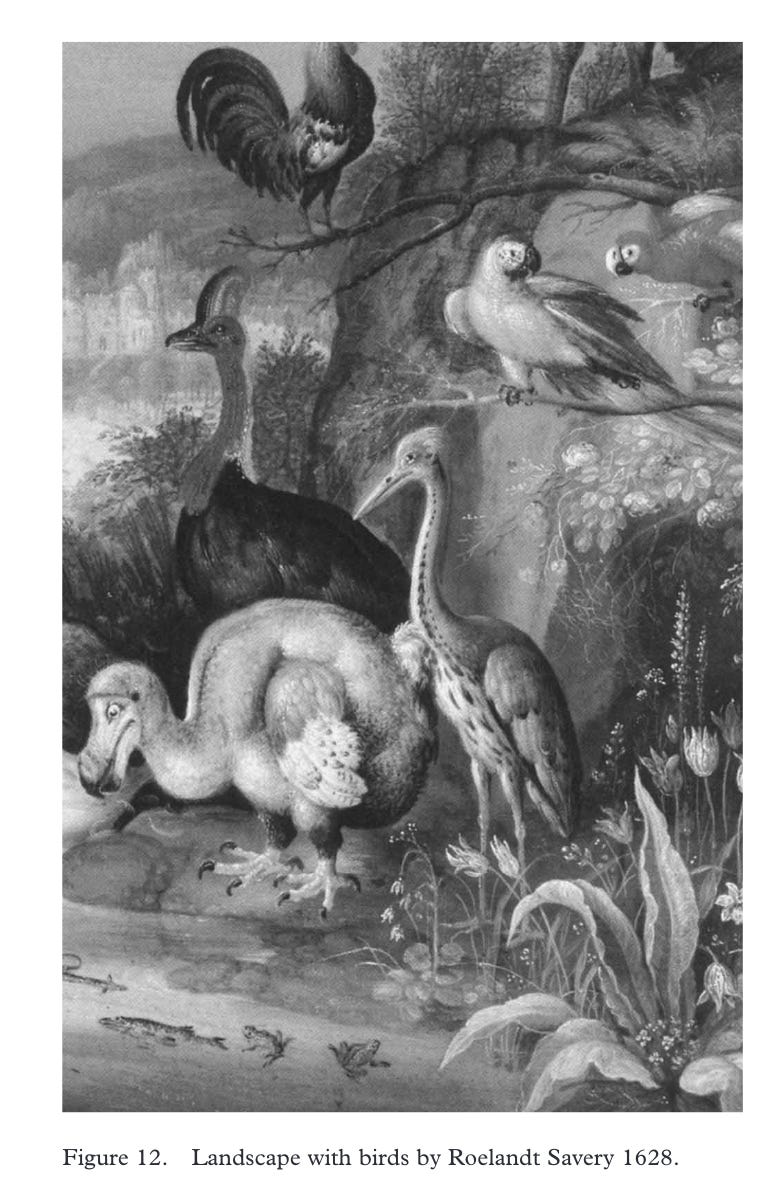

Dodos lived with other recently extinct Mauritian birds, such as the flightless red rail (Aphanapteryx bonasia), the broad-billed parrot (Lophopsittacus mauritianus), the saddle-backed Mauritius giant tortoise (Cylindraspis inepta), and many more species. Sadly, human intervention, from hunting, deforestation, and the introduction of invasive species, led these animals to extinction.

The Biology and Ecology Of The Dodo

Little is known about the behavior of this feathered friend.

In the beginning, as we saw in the first ever written report of dodos, it was thought that they were penguins. Then, early scientists proposed they were some kind of small ostrich, albatross, or vulture. In 1842, however, Reinhardt proposed dodos were pigeons, which was later confirmed, with the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) being its closest living relative (Soares et al., 2016).

You may wonder why we know so little about the Dodo despite being superstars.

Well, this is because most dodos reports come from letters. They are very brief. However, we know from fossils, art, and letters that these birds had tiny wings but robust legs, making some scientists suggest they could run quite fast. Their beak was strong and their principal “weapon,“ although it is generally agreed that these birds had no real reason to be aggressive, as they had little competition and no predators.

As a neuroscientist, a question that intrigues me is if these animals were smart. Luckily, we had some evidence for this. In 2016, scientists published a scientific article showing that the brain-body-size ratio of dodos was similar to that of modern pigeons (Gold et al., 2016). This suggests that these flightless birds were probably equal in intelligence!

What Made The Dodo Go Extinct?

It is estimated that dodos lived until 1690 (Roberts & Solow, 2003).

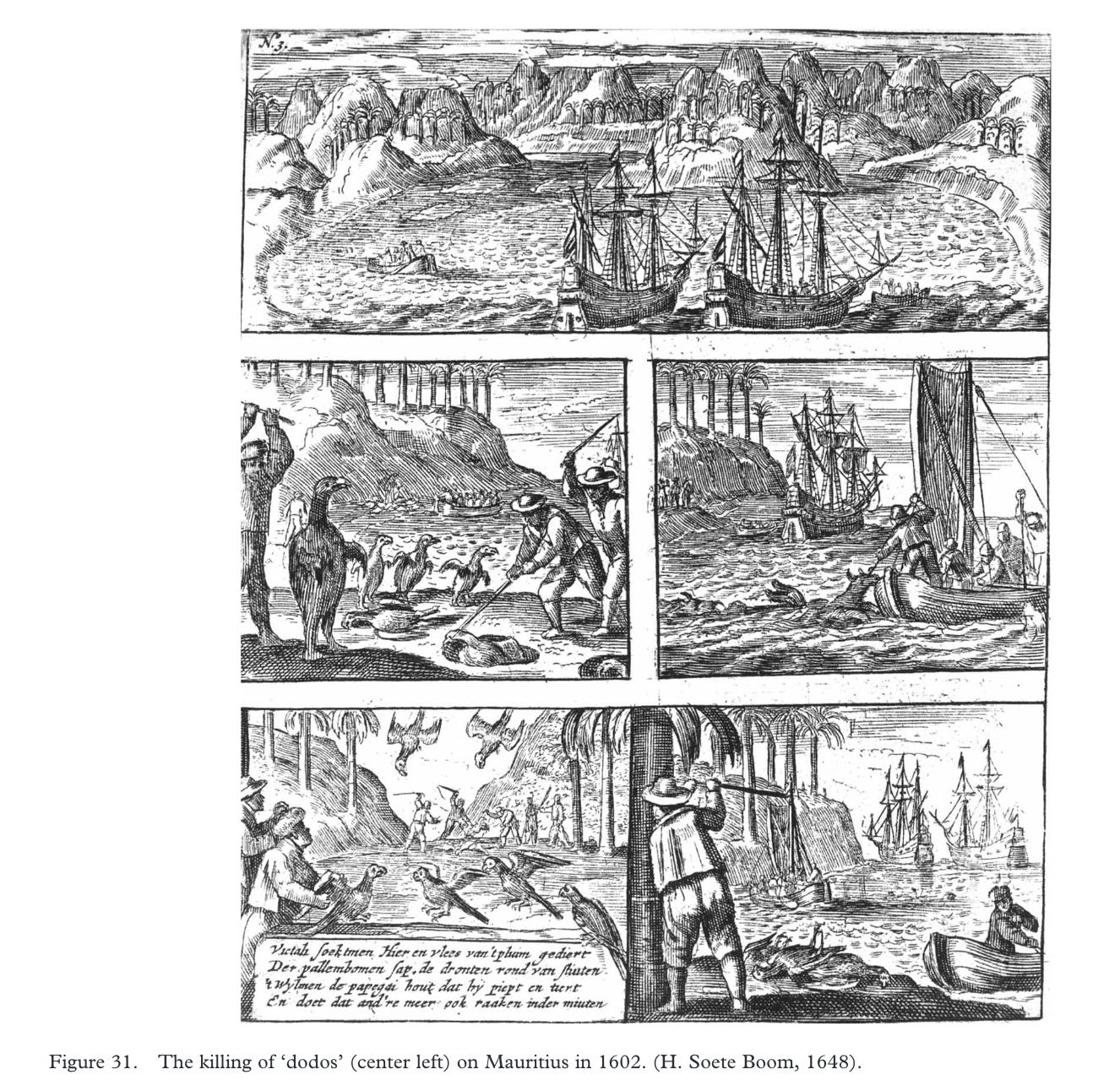

This is tragic. It took only 92 years after the arrival of the Dutch to eradicate the existence of dodos. Although the exact reasons for this are still debated, the most accepted one is that multiple causes led these giant pigeons to extinction, with hunting only one of its causes.

Until the arrival of humans, dodos faced no predators, making them fearless and easy targets for hunting. However, this was only the beginning of hell for these birds. Because we introduced invasive species, such as rats, pigs, and monkeys, that created a domino effect with devasting consequences for Mauritius.

Hume (2006) reports letters from the Dutch mentioning how their ships had rats that eventually joined the island. These animals used to feed on bird’s eggs, making it harder for dodos to keep reproducing, something New Zealand’s birds, for example, are still struggling with, with many already extinct.

Additionally, Europeans transported pigs in their expeditions, and they are well known for destroying ecosystems. The destruction of native forests has reduced the availability of nesting sites and food sources, which is happening with cassowaries in Australia.

These animals also started to compete for resources, and as the Dodo evolved without predators and competition, their numbers started to decline more and more until it was declared extinct. Less than a century after its discovery.

Can We Bring Them Back To Life?

Colossal Biosciences, a biotechnology company, is trying to bring back animals from extinction (Callaway, 2023).

And one of their first targets is the Dodo.

They plan to isolate and culture specialized primordial germ cells (PGCs), which make sperm and egg-producing cells from the dodo’s closest living relative, the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica). Then, scientists would edit DNA sequences in the PGCs to match those of dodos using CRISPR. Next, these gene-edited PGCs would then be inserted into embryos from a bird species to generate chimeric animals, which could produce something resembling a dodo.

Can this happen? Theoretically, yes.

Is it going to be easy? Of course not.

Their plan would depend on huge advances in fields like gene editing, stem cell biology, and more. However, even if this comes to reality, is bringing an extinct species back to life ethical?

Mauritius is no longer the paradise dodos used to live in.

Isn’t it better to use that money and effort to save the current species that are highly threatened there because of humans?

What do you think?

If you liked our article, share it with your friends. That helps Cognitive Creatures growing up :) And why not get a Dodo? If you buy it through this link, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Long live the Dodo!

“With a greater sense of understanding comes a greater sense of wonder”. — Anil Seth.

Until the next time,

Axel and Victoria.

📚 References

Barnwell, P. J. (1948). Visits and despatches 1598–1948. Begin en de voortgangh van de vereenighde nederlandtsche geoctroyeerde oost-indische compagnie, vervattende de voomaemste reysen... Gedruckt in den jaere (1646). Port Louis, Mauritius: Standard Printing Establishment.

Callaway, E. (2023). What it would take to bring back the dodo. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00379-5

Gold, M. E., Bourdon, E., & Norell, M. A. (2016). The first endocast of the extinct dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and an anatomical comparison amongst close relatives (Aves, Columbiformes). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 177(4), 950-963. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12388

Hume, J. P. (2006). The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius. Historical Biology, 18(2), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912960600639400

Moree, P. (1998). A concise history of Dutch Mauritius, 1598 – 1710. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. p 127.

North-Coombes, A. (1971). The Island of Rodrigues. Port Louis, Mauritius: The Standard Printing Establishment (Henry & Co.). p 338.

Roberts, D. L., & Solow, A. R. (2003). When did the dodo become extinct? Nature, 426(6964), 245. https://doi.org/10.1038/426245a

Soares, A.E.R., Novak, B.J., Haile, J. et al. (2016). Complete mitochondrial genomes of living and extinct pigeons revise the timing of the columbiform radiation. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 16, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0800-3